Chapter 11 No mussels in patches

Dave Strayer

Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, New York, U.S.A.

Every so often, you hear about that mythological creature, the scientist who has never had a paper rejected. Most of us, though, begin to accumulate rejections as soon as we begin to submit papers. I myself have been rejected by ~20 different journals, from Science to the Northeastern Naturalist. I’ve gotten rude reviews, kind reviews, superficial reviews, insightful reviews, and just-plain-wrong reviews. Editors have made fair decisions about most of my papers, but have rejected some of my best papers, and accepted some papers that probably needed work. Not surprisingly, it’s the rejections, rather than the easy passes, that we authors remember.

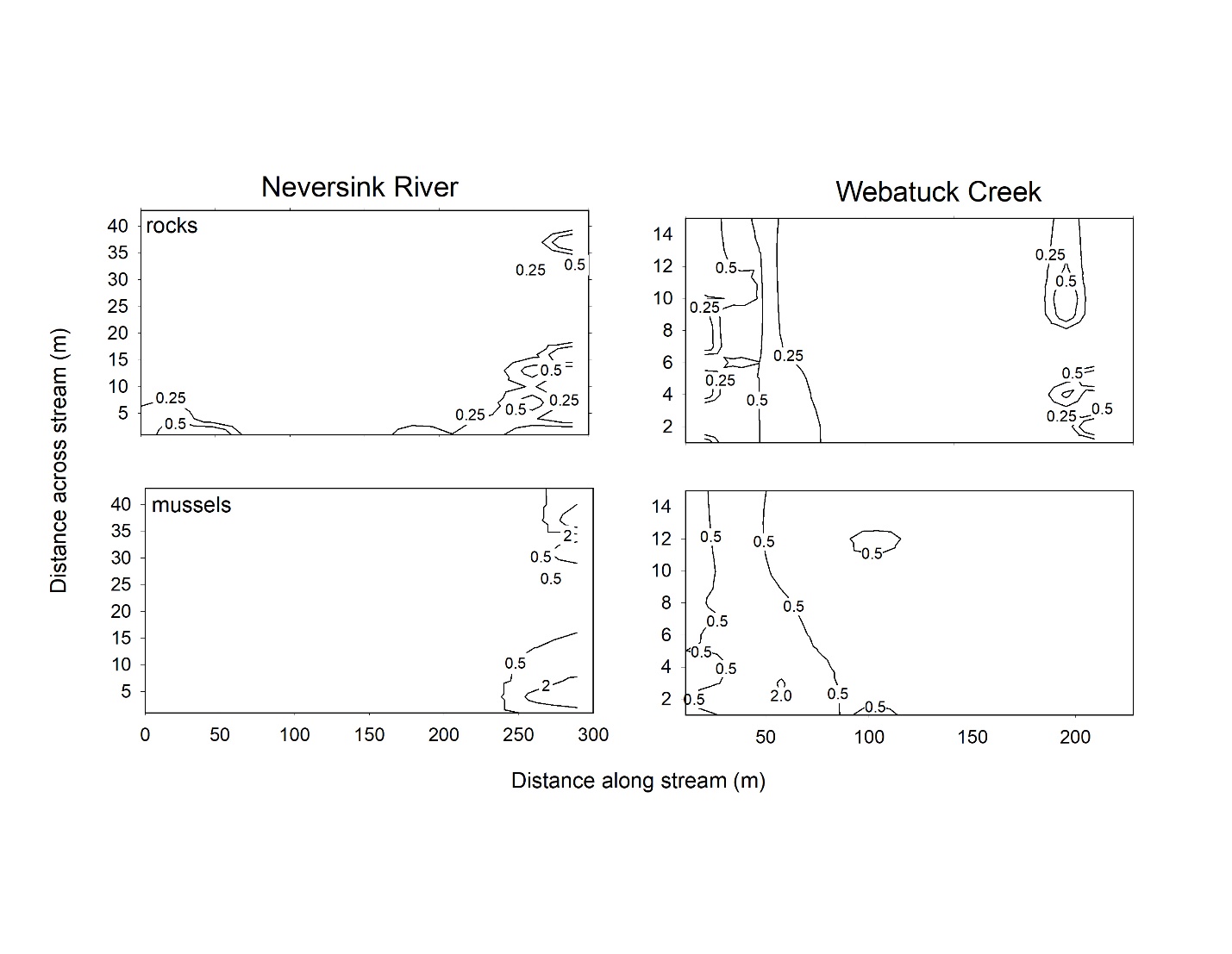

Each rejected paper has its own story. I’ve chosen to tell the story of what I think of as one of my best papers (Strayer, 1999), which was soundly rejected, twice. Freshwater mussels (Figure 11.1) are distributed very patchily in streams (Figure 11.2 bottom panels); some small patches on the streambed contain lots of mussels, but large areas support few or no mussels. Previous papers (e.g. Strayer & Ralley, 1993) had shown that conventional explanations for local distribution of stream macroinvertebrates (e.g., current speed, sediment grain size) failed to account for mussel distribution.

FIGURE 11.1: The brook floater (Alasmidonta varicosa). One of the mussel species living at the Neversink River study site.

I had the idea that local differences in disturbance severity and frequency might account for mussel distributions. Mussels are long-lived (typically 5-50 years, Haag, 2012) compared to the frequency of floods strong enough to move stream sediments (floods typically mobilize stream sediments every 1-2 years). Maybe mussels live on little bits of the streambed that are stable during floods.

I thought that we could test this idea by marking stones on the streambed, waiting for a flood, and seeing whether the marked stones survived in the mussel patches but were swept away elsewhere. My faithful assistants marked and set out thousands of stones into two small rivers (Figure 11.3) with mapped patches of mussels – so much work! As luck would have it, we got big floods the first winter, and the results strongly supported our idea – we recovered marked rocks in the mussel beds but few elsewhere (Figure 11.2).

FIGURE 11.2: The results of counting mussels. Probability of a marked rock remaining in place through a flood (upper panels) and mussel density (number/m2) in two small rivers in New York, modified from Strayer (1999). Note the spatial coincidence between the distributions of rocks and mussels.

I thought this was a really good study - so I wrote it up and sent it to Freshwater Biology. The journal flatly rejected it – not revise and resubmit, not send to a different journal, but reject. The criticisms all looked either wrong or addressable to me. One reviewer objected to the absence of statistical testing of what I thought was an obvious match of rock and mussel distributions, so I invented what I thought was a nifty new statistical test (independently proposed by Roxburgh & Chesson, 1998) and added it to the paper. I thought that the paper was even better, and a good match to the journal, so I wrote back to the editor, asking him to reconsider the paper. He agreed, and the revised paper went out to review, only to be once again rejected.

This might have been a good point to give up on the paper, or at least radically rework it. But even with the benefit of two sets of negative reviews and editor’s comments, I still thought that this paper was fundamentally sound, so I revised it once more, and sent it to the Journal of the North American Benthological Society. They accepted it after minor revision and published it without incident.

The paper has been a modest success, with 281 cites on Google Scholar and 131 cites on Web of Science, as of 21 Aug 2021. Gratifyingly, citation rates have been rising, with the highest citation rates yet occurring 20 years after publication. I flatter myself into thinking that perhaps this twice-rejected paper has thus either inspired or anticipated mussel research over the past couple of decades.

11.1 Figure out how to handle rejections

If you’re an academic researcher, your proposals and papers are going to get rejected, fairly or unfairly, so you should figure out how to handle and even benefit from rejections, rather than stewing over them and letting them harm your life and career. Here are a few things that have helped me.

I’ve learned that it’s always worth thinking carefully about the feedback that you get, even if it is harshly negative. Reviews often include good advice for improving your paper (like adding that statistical test). If a review contains criticism that is off-base or wrong, I’ve learned to ask myself whether poor communication on my part, and not just stupidity on the reviewer’s part, might have led to the unwarranted criticism. I’ve been dismayed at how often I’ve found unclear writing when I went back to look at a criticized paper. Better communicating your results and ideas can keep future readers from making the same mistake that the reviewer did. Finally, I’ve learned that it’s ok to reject and ignore criticisms that are unfair or irrelevant – reviewers are not always right! But you should reach this conclusion only after you have carefully thought about the reviews, with as open a mind as is possible. As a corollary to this, I learned never to write a response to reviews or resubmit a paper right after I get the reviews, when I’m still hot and most want to write that response. Now, I read the reviews, put everything aside for a week, then get to the hard work of deciding how to respond.

I’ve learned not to give up on a rejected paper if I’m convinced of its value, even after negative reviews. Some of my favorite papers were first rejected (Strayer, 1983; Strayer, 1999 and more; Strayer, Hattala & Kahnle, 2004; e.g. Strayer & Malcom, 2006; Strayer, 2020), but I was able to use what I learned from these initial rejections to improve the papers and publish them, sometimes in a better journal.

I’ve learned that once a paper has been rejected by a journal, it’s probably best to move on to another journal, rather than persisting with the first journal. I have heard of cases where a journal reversed a decision about rejection, but it’s rare, and it never happened to me. More often, going back to the original journal led to further delays and frustration. There are plenty of good journals for your work.

FIGURE 11.3: Mussels occur in patches in streams. One of the study sites, Webatuck Creek, during typical summer water levels (left) and during a late-summer flood (right).

11.2 The hard part

The hard part, which I still struggle with, is knowing whether to listen to expert voices saying that your work is flawed or worthless, or to your inner voice saying that your work is good or important. Critics, even eminent ones, can be wrong, and we all know of examples where only an author’s persistence saved a great piece of work from oblivion. James Joyce sent his Dubliners, now considered to be one of the greatest short story collections in the English language, 18 times to 15 different publishers over a nine-year period before it was finally published. So maybe your rejected work really is good (though probably not as good as Dubliners), and you should revise and resubmit it as many times as it takes to get funded or published.

On the other hand, I know of plenty of examples in which a scientist (sometimes me!) wasted a lot of time pushing a stale or flawed idea that didn’t deserve to be published. It’s easy to overvalue the novelty and importance of your own work. Pursuing a bad or mediocre manuscript can waste time that you don’t have to waste as an early career scientist, and harm your reputation among colleagues.

I can offer only two suggestions to help you balance your inner voice and the outer critics. First, if you can, find out whether you tend to overvalue or undervalue your own work. This can help you decide whether you need to adjust the volume of your inner voice up or down. Second, try to find one or a few people who have the good judgement, good will, and time to serve as an honest critic of your ideas. Such people are hard to find, but can be invaluable, especially if you can keep them over the course of your career. But in the end, you will need to make your own hard decisions about whether the negative critics are right, and when to give up or sink more time into rejected proposals and papers.