Chapter 6 A long tail

John R. Hutchinson

Structure & Motion Laboratory, Department of Comparative Biomedical Sciences, The Royal Veterinary College, London, United Kingdom

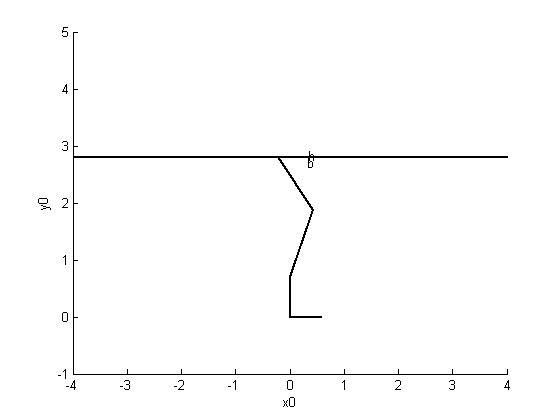

I’m an evolutionary biomechanist; I study how major transitions in locomotor function in vertebrates with limbs have evolved, and often how body size (e.g., gigantism) has played a role in that evolution. So it might come as no surprise that I’ve studied dinosaurs. They evolved a huge range of sizes and many forms of locomotion or unusual anatomies that provoke questions about how they functioned or how those functions were transformed. My career as a PhD student began by tackling the question of how the famous gigantic theropod (carnivorous, bipedal) dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex moved, especially if it could have been fast as some palaeontologists had argued (against expectations from basic biomechanics or patterns in living mammals). We used very simple two-dimensional (2D) biomechanical models (Figure 6.1) to test how big T. rex’s leg muscles needed to be to enable fast running, finding that previously claimed speeds >25 mph or so; or especially racehorse-like speeds ~40 mph; were implausible. It is very fair to say that the resulting paper I published in Nature (Hutchinson & Garcia, 2002) with an engineer co-author (thanks to quite supportive peer reviews) is to credit for much of my early career success, and thus for where I am now in my career, too; I’ve gotten a lot of mileage out of it.

FIGURE 6.1: An old school T. rex model. 2D model of a right hindlimb used to estimate how large muscles needed to be to sustain fast running. Contrast with the anatomical realism of figure 6.2.

But I grew to want to move on from T. rex in my career. Frankly, I got tired of T. rex over the years, fascinating as it remains from a biomechanics standpoint (how can a 7000+ kg biped stand and move?). What truly got me excited was how the locomotion of early dinosaurs evolved (back in the Triassic >200 Mya; not the end-Cretaceous ~66 Mya); such as how they became bipeds in the first place, and how their locomotion differed from other, closely related Triassic animals that were forebears to crocodiles. I was lucky (and privileged) again, getting a five-year European Research Council Advanced Investigator Grant (called “DAWNDINOS”) to study these questions, and do so using cutting-edge 3D biomechanical simulations that were far more anatomically, physiologically and physically realistic than in my PhD work; and set in an explicitly evolutionary context.

That DAWNDINOS grant work led tortuously along that cutting edge of 3D simulations. Now acting as a Professor and project manager, very unlike my PhD experience, I learned a lot about what I did not know about the methods we tackled, finding myself deep in the learning curve. It was tough for all of us involved. Finally though, after over two years we made some key progress, and that was because I helped link our team up with external collaborators who really knew those cutting edge simulation methods (developed for studying human locomotion), and they trained my postdoc in those simulation tools. We became able to do what I’d wanted to do for my whole career: to build a 3D musculoskeletal model of an extinct dinosaur and estimate how it could, or could not, have moved, using what is called predictive simulation: setting a task for a computer model, given certain inputs or constraints, and having it solve that problem with ‘optimal control theory’ (e.g., running as quickly as possible). Importantly, we showed in a series of papers that we could do this fairly well (obtaining simulation results that matched experimental measurements) for a living dinosaur; a bird (Bishop et al., 2021b; Bishop et al., 2021c); and that we had a fairly objective, repeatable methodology for making these 3D models in the first place (Bishop, Cuff & Hutchinson, 2021).

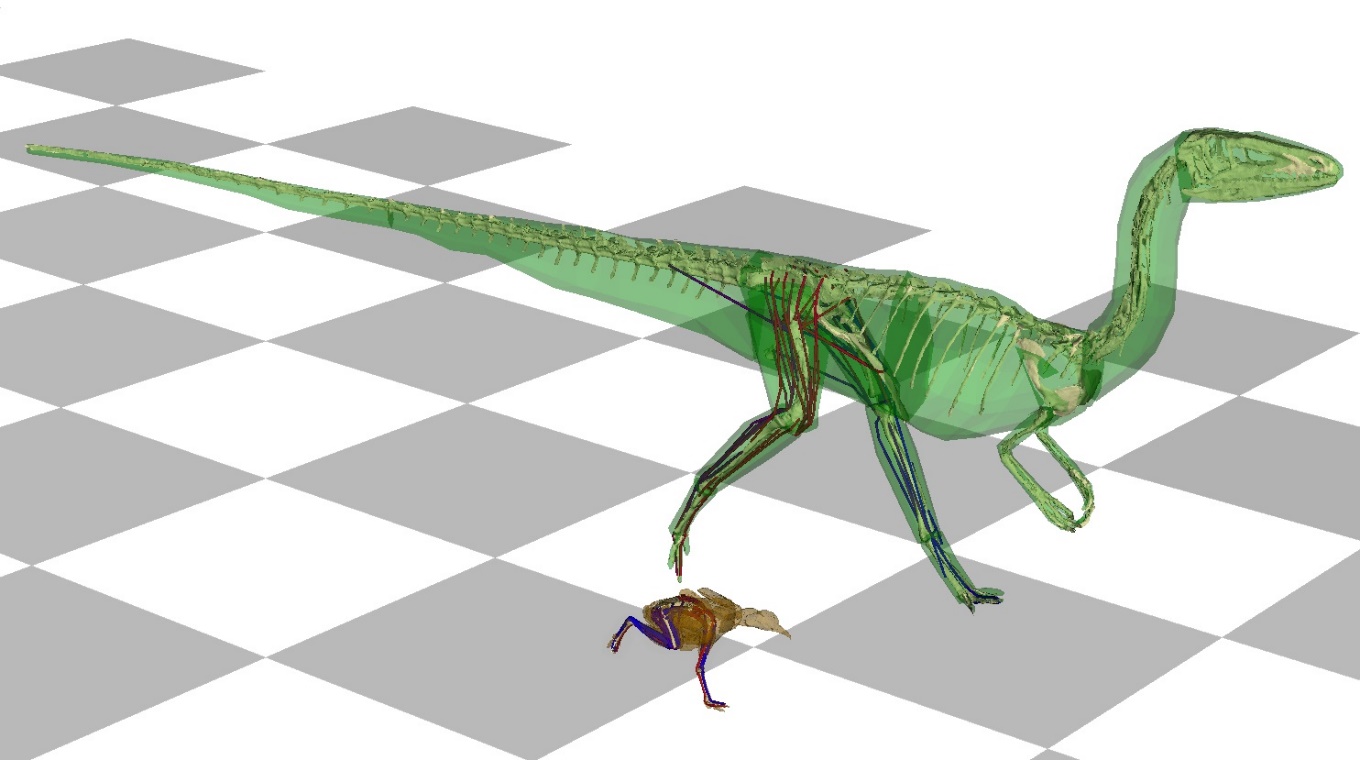

So we chose a fairly unprepossessing but well studied theropod, Coelophysis bauri (~15 kg biped from ~210 Mya) for our first predictive simulations of an extinct dinosaur’s locomotion. Admittedly this was purely exploratory work at first. We just wanted to see what it would do if we asked the simulation to run quickly. It was comforting to find that it produced speeds commensurate with our prior estimates from simpler methods, and it produced forces and motions that matched other independent predictions reasonably well, too. Then, serendipitously, my postdoc was inspecting the output motions of the simulation and realised that the long tail was moving in a consistent, conspicuous pattern. Cleverly, he noticed that as the hindlimb swung backwards with each step, the tail swung toward it. Inspecting more deeply, and using the power of the simulation to change different things such as swing the tail the ‘wrong’ way or have a heavier tail, he found that the tail of Coelophysis was being used by the simulation to regulate the angular momentum of the whole animal, in an important way; much like humans swing their arms when they walk (Figure 6.2). This regulation makes locomotion more efficient and stable, and arises from the simple physics of motion; not from underlying physiology per se. The postdoc called this “some pretty exciting results!” and we all agreed, deciding to pitch this study to a ‘high profile’ journal.

6.1 Submitting the manuscript

We submitted our paper to Science on 30 October 2020 and got the desk-rejection notice from the editor on 10 November 2020; “not one of the most competitive in terms of general interest” studies, we were told. Disappointed but undeterred, we tried Nature (22 November 2020 submission) and received another desk-rejection on 30 November 2020, but with the offer of a transfer to their journal Nature Communications, promising peer review there. We received those reviews 30 March 2021, and the result was rejection. Two reviewers were enthusiastically supportive, urging fairly modest revisions, but a third was unconvinced—conceding that “this work probably represents the state of the art” but they did not feel that the method was mature enough to apply to extinct animals. They seem to have approached the review from the perspective of someone familiar with how these cutting-edge simulations are used for studying human locomotion (and how those have their own, debatable faults), not taking into account that the same standards might not be achievable for other species (living or extinct), yet good progress might still be achievable. But they weren’t wrong, either; it is just human nature that views on what is ‘good enough’ in science will differ. As the reviewer acknowledged, “And this is a largely qualitative judgement call.” Frustrated, we regrouped and resubmitted, with some clarifications in the manuscript about what the simulations could and could not do (and a simulation in which we digitally cut off the tail, showing that it did make a difference), to Science Advances, on 30 March 2021. We obtained constructive reviews with modest revisions, and on 30 July 2021 we were thrilled to obtain the “accept” decision email (Bishop et al., 2021a)!

FIGURE 6.2: Modern computer 3D simulations of running locomotion. Running locomotion in a modern tinamou bird (Eudromia elegans, brown) and extinct theropod dinosaur (Coelophysis bauri, green). Grey tiles = 50 cm. By Peter Bishop.

6.2 Looking back

I’ve had plenty of truly terrible experiences with peer review in my career, such as reviewers “screaming” in all-caps or accusing me of bias/conspiracy without any basis. Those kinds of personal attacks are (rare as they are for me; thankfully), as a seasoned veteran, relatively easy for me to shrug off as unprofessionalism. It can be hard, though, in a different way, to accept the loss of control in peer review, as in much of life. My experience with this paper exemplifies how subjective decisions on novelty or broad appeal by editors at ‘glamour mags’ and by peer reviewers on those aspects as well as technical soundness (which can happen at any journal) are an aspect of peer review that we live with. “Innocent, unbiased observation is a myth” (medawar1969induction?) applies to job, grant and peer review as it does in so many other realms of human existence. There is randomness, arbitrariness, chaos and unconscious bias that may never be fully extracted from science because humans, not robots (so far), do science. Accepting these facets of science is akin to accepting the existence of an uncaring universe; it is hard. I didn’t learn that lesson from this paper; it is something I’ve just struggled with throughout my career and life. And that struggle will continue. That is not at all to say we cannot improve peer review; there are ways, for example, to reduce the impact of biases (e.g. D’Andrea & O’Dwyer, 2017); and we can do our best ourselves when we conduct editing and peer review.

For early career scientists, I recommend working on accepting that lack of control; it is a valuable life skill. Focus on what you can control; not the yawning void of demoralising uncertainty. A rejection might include hints (or even nicely constructive reviews, which we broadly obtained) of what to change. It’s natural to at first rage against a decision that you feel is unfair. Yet, as your passions cool, take the opportunity to calmly inspect what might be improved: maybe you didn’t explain some complex methodology well enough, so perhaps some extra text or a ‘workflow’ figure could help future reviewers and readers understand? Maybe that expert reviewer who misconstrued your analysis did so because you assumed very specialised understanding of your analysis and even just an extra sentence or so could help justify your analysis? You probably know your science best, but that can be to your detriment in peer review: re-read what you’ve stated by putting your mind in the role of a reader who does not know your science as well as you do. Especially if you’re working on some cutting edge of your science, you may lose people off that edge if they can’t be led by your manuscript safely along that frontier. And be patient; expect that the process might be slow (especially in these days of the COVID-19 pandemic) but persistence and resilience can still pay off. If you believe in your science, your work will find a home somewhere. Celebrate when it does.