Chapter 5 The challenges of publishing novel research

Matt W. Hayward 1, 2, 3

1Conservation Science Research Group, School of Environmental and Life Sciences, University of Newcastle, Callaghan 2308 NSW Australia; 2Centre for Wildlife Management, University of Pretoria, Tshwane X001 South Africa; 3Centre for African Conservation Ecology, Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa matthew.hayward@newcastle.edu.au

5.1 Introduction

In 2003, I moved to South Africa from Australia to take up a post-doctoral fellowship with Graham Kerley at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University to research the reintroduction of large predators to Addo Elephant National Park (Addo). This was part of several predator translocations that were occurring throughout the Eastern Cape Province at that time (Hayward et al., 2007a). I had finished my PhD six months earlier on the conservation ecology of the quokka Setonix brachyurus in the Western Australian jarrah forest, and had just completed a short post-doc at the Walter Sisulu University (also in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa), when I moved down to live in the research area of the staff village in Addo.

I lived in a 3m x 4m hut (known as a ‘Wendy’ hut, because it was only big enough to fit Peter Pan and Wendy; Figure 5.1). With me in the research area, there was a team of black rhino Diceros bicornis researchers from New Zealand, an elephant Loxodonta africana researcher from Ireland, and some German’s researching southern red bishops Euplectes orix.

FIGURE 5.1: Life inside a 3m x 4m uninsulated Wendy hut in Addo Elephant National Park in mid-summer. My research assistant was at pains to model an authentic South African National Parks towel in all its glory.

In November 2003, six lions Panthera leo were released from soft release bomas into the Addo Main Camp section. My job was to determine how they fared and what the impacts were. It was an amazing experience. We were fully immersed in our study species. Generally, I would drive out each morning to see what the lions had been up to overnight – as each had radio collars (Figures 5.2 and 5.3). Twice each season my girlfriend (now wife Gina) and I would live in the back of our research vehicle for 5 consecutive days following individuals as this is the most robust way to determine their diet, movements and what species they encounter (Mills, 1992). We also drove transects each season to determine the density of all potential prey species. We fell in love with South Africa and its people.

FIGURE 5.2: Each day my wife, Gina, and I would venture out into Addo Elephant National Park to see what the lions had killed. We also performed continuous follows where we lived in the vehicle for 96 consecutive hours to determine the movement patterns, hunting success rates, prey encounter rates and diet of the lions and spotted hyaenas.

5.2 Back story

Very soon after the release of the lions, I started finding Cape buffalo Synceros caffer carcasses. The lions had been translocated from the Kalahari-Gemsbok National Park about 1000 km to the north, and which is a very different (desert) biome to that found at Addo (sub-tropical thicket biome). Hence, we were unsure of what they would eat, and one of the first conversations I had with the regional manager of South African National Parks, Lucius Moolman, was what their diet would be in Addo.

Coming from Australia, I had pretty much no idea what they’d eat, so I stupidly assured Lucius that they’d probably eat what they had eaten in the Kalahari. He shook his head and patiently said “Matt, those lions come from the Kalahari. None of the animals they ate up there live down here”. So I thought some more, and offered the suggestion that I’d read that lions were generalist predators (Schaller, 1972) and hence they would probably eat the most abundant species in Addo. Again, Lucius shook his head and highlighted that elephants were one of the most abundant species in Addo, and he couldn’t see the lions focusing on them. So I set about doing some research to answer Lucius’ question. I thought that if I could determine what lions prefer to prey on throughout the rest of their distribution, it would give me a good idea of what they would eat in Addo. Over the next 6 months, I reviewed the literature on lion diets and related what they killed to the available prey at each study site. I discovered that lions kill five species more frequently than you would expect based on their relative abundance within the prey communities where they exist: blue wildebeest Connochaetes taurinus, plain’s zebra Equus quagga, giraffe Giraffa cameleopardalis, Cape buffalo, and gemsbok Oryx gemsbok, and they prefer prey weighing between 90 and 550 kg (Hayward & Kerley, 2008).

I thought this was a great discovery. Now I could predict the diet of lions at Addo (which we subsequently did with high accuracy; Hayward et al. (2007b)). Graham reviewed the paper and was happy to be a co-author, so I submitted it (I think it was to the Journal of Animal Ecology). I thought the research was internationally relevant and important in that it offered a way to predict the diet of a predator and the methods could be used for all other large predators that had been sufficiently studied. It got desk rejected without being sent for review. I then submitted it to other international journals (I think Journal of Applied Ecology, Oikos, Proceedings of the Royal Society, Ecology and a couple of others). It was massively disheartening with most rejections being because the results were not considered of ‘international importance’.

After almost a year, we submitted the manuscript to the Journal of Zoology and got two excellent reviews – one by an anonymous referee and the other by Rob Slotow. The reviews were excellent because they were critical but offered specific advice on how to improve the manuscript. These were not methodological changes, but rather ways to emphasise the international relevance of our work. We did this and the paper was finally published in 2005: Hayward & Kerley (2005).

FIGURE 5.3: All reintroduced predators were fitted with radio collars. This female (Kamqua) was the first to successfully breed in Addo for over 100 years, and the park staff generously named her cubs after my wife and I.

5.3 The outcome

Since publishing that first paper on lion prey preferences (Hayward & Kerley, 2005), I recognised the important results it yielded on the critical prey requirements of the lion and that this would be important knowledge to help conserve all large predators. Hence, I expanded this field of research by investigating other large predators in Africa from leopards Panthera pardus (Hayward et al., 2006c), to cheetahs Acinonyx jubatus (Hayward et al., 2006b), spotted hyaenas Crocuta crocuta (Hayward et al., 2006a), African wild dogs Lycaon pictus (Hayward et al., 2006c), and jackals (Hayward et al., 2017; Hayward et al., 2018). When you’re on a winner, you should stick to it – so I extended the species studied to large predators on other continents, including tigers Panthera tigris (Hayward, Jędrzejewski & Jêdrzejewska, 2012), dholes Cuon alpinus (Hayward, Lyngdoh & Habib, 2014), and jaguars Panthera onca (Hayward et al., 2016). I have also had students or collaborators who have extended this research to chimpanzees Pan troglodytes (Bugir, Butynski & Hayward, 2021), snow leopards Panthera uncia (Lyngdoh et al., 2014), wolves Canis lupus (Jędrzejewski et al., 2012), brown bears Ursus arctos (Niedziałkowska et al., 2019), Pleistocene predators (Valkenburgh et al., 2016) and even humans (Bugir et al., 2021). This research has led to an ability to accurately predict the diet of lions (Hayward et al., 2007b), and determine the number of large African predators that can be sustained at a site based on the available prey communities (Hayward, O’Brien & Kerley, 2007; Hayward & Kerley, 2008). The relationships we discovered between the biomass of preferred prey species and prey within the preferred weight range of lions, leopards and spotted hyaenas has enabled us to determine whether fencing constrains their movements in fenced conservation areas (Hayward et al., 2008). We were also able to reinforce the validity of our results by illustrating that the prey preferences lions exhibit are reinforced throughout the predatory behavioural sequence (Hayward et al., 2011).

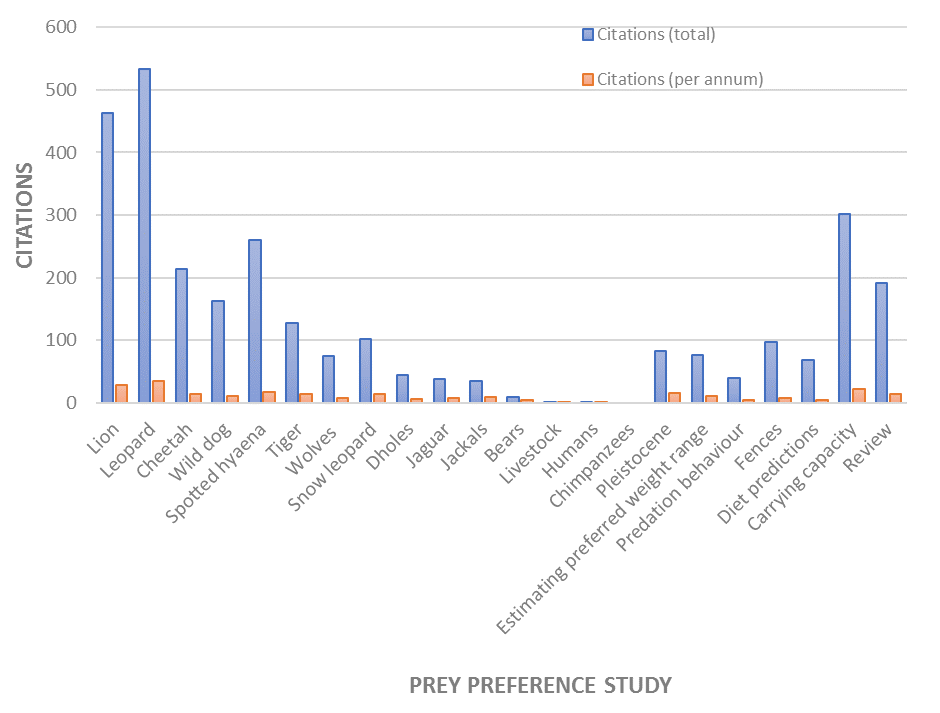

These papers have been cited almost 3000 times on Google Scholar since 2005, and amass over 180 citations each year (Figure 5.4). Our discoveries have now led to our predictions of carrying capacity to be used in fenced reserves throughout southern Africa (Ferreira & Hofmeyr, 2014), and are being implemented as a way of estimating the number of tigers that can be sustained in tiger sanctuaries in India (Y.V. Jhala, Wildlife Institute of India, pers. comm.). The research has also been acknowledged as some of the few that has yielded real benefits to carnivore conservation (Balme et al., 2014).

FIGURE 5.4: Total citations and citations per year of studies that have arisen because of the methods developed in the initial lion prey preferences paper (Hayward & Kerley, 2005). The different species studied are shown along the x-axis while citations (total blue and per annum red) are shown on the y-axis (at the time of writing in September 2021).

5.4 Advice to Early Career Researchers

My main advice to people new to academic publishing is to treat publishing as a game – don’t take rejections to heart. It really shouldn’t be taken too seriously given you have to firstly convince a single Editor to send your manuscript for review. That person may have no idea about your field, or may be having a bad day. They may just miss the point. This is not a metric upon which to base your personal value of your scientific quality. Then you need two referees to view your manuscript supportively. So essentially there are three people you need to satisfy to get your paper published. This is a very small sample size, and they could easily be wrong. Don’t give up. If they aren’t pointing out major methodological problems with your work, don’t panic. Use their advice to improve the manuscript, and keep going. The real test is whether your peers see value in your work by citing it – and at ~180 citations per year, I’m comfortable the methods are robust and the conclusions valid.

I would urge you also to use the referees comments to improve your work. Go through every single comment and, if it is valid, change your manuscript accordingly. Be brave enough to stick to your guns if you disagree, but remember that the referees are likely to be well regarded in the field, so they probably know a thing or two. Hopefully they will be specific in their comments to illustrate exactly what needs to change and how. Use their expertise to your benefit – even if they are mean.

5.5 Another final twist

The ecological world seems satisfied with the prey preference research, now readily accepting the methods we have employed on a broad suite of animals. Recently, I took on a student to expand this field of research to look at the prey preferences of hominids – Neanderthals Homo neanderthalensis and anatomically modern humans H. sapiens. The journals she has sent these manuscripts to are largely archaeological and palaeontological (Journal of Human Evolution for example) – and we are getting the same kinds of blow-back. Comments questioning the accuracy of the results because at the site the referee works Neanderthals prefer shellfish rather than large animals, for example, are made. We still get similar concerns raised with our carnivore results on the same grounds – indicating a lack of comprehension that a result from a single site is an anecdote, compared to results from multiple sites throughout a species’ range.

My PhD student is disheartened by these rejections. Sadly, I’ve been here before.