Chapter 4 Hypothesis Building

When we reach Week 4 and look at the formula of writing a chapter (see Week 4) you will see that everything in your chapter or paper revolves around the hypothesis or questions that you ask, normally at the end of your introduction (Figure 6.2). In this section, we will take a look at how to build a hypothesis. This is a sticking point for many students. We are used to using and writing questions and statements in day-to-day communications, as well as reading popular media. But hypotheses (the plural of hypothesis) very rarely come into regular conversations. So how do we write one, and how do we know if our hypothesis is good?

In addition to this section, there is some good information out there on the web, and it’s worth looking at this too: (e.g. Wikihow, Wikipedia, etc.). There’s also some less good stuff out there, so read critically. If you know of some really good sites in your language, then please let me know so that I can share them here.

4.1 Aims of this workshop

In this workshop, you will find three exercises that aim to help you:

- find the hypothesis being tested in a research paper

- determine the components that make up the hypothesis and see how they are introduced

- evaluate the hypothesis and determine whether or not it meets the criteria of having independent variables, a mechanism supported by the literature, and if it is falsifiable

In each of these exercises you will need to use the five research papers that you used in previous exercises (see here). You should now be getting used to the idea that these five papers are going to be very important in this course, and that the more relevant they are to your own project, the more useful the course will be to you.

4.1.1 What is a hypothesis?

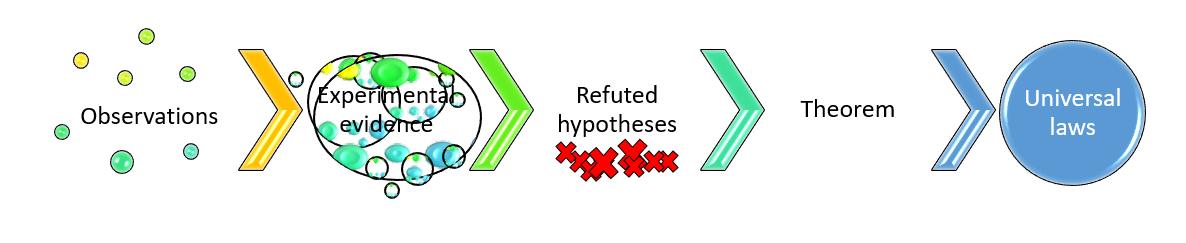

A hypothesis is a statement of your research intent. It tells the reader, what you plan to do in your research. But there’s a little more to it than this. The hypothesis becomes a part of the scientific method as it is testable and (importantly) falsifiable, and it is informed from previously published work on the subject. By building and refuting hypotheses in the biological sciences, we can eventually establish theories that unify sets of hypotheses that have not been falsified (see Figure 4.1). Although they are absent in the biological sciences, universal laws come from theories that can logically be shown to be correct in every circumstance. However, a fundamental part of all science is that both theories and laws are ultimately refutable.

FIGURE 4.1: Working with hypotheses is the only way toward generating working theories. Although universal laws are only considered in mathematics and physics, we still use theories in the biological sciences. The best way towards establishing more useful theories is through working to refute hypotheses.

Your hypothesis must be informed by the literature, which is why you will spend so much time and effort crafting your introduction to inform your reader about all the components of your hypothesis. This is also why your hypothesis usually comes at the end of your introduction, because you spend all of the introduction telling your reader about it. There’s not much point in writing more after the hypothesis, because once your reader has read that, they are ready to learn about how you went about testing it (in the Materials & Methods). The other important point to make is that the literature should dictate how you write your hypothesis, and the variables that you include. If, for example, you think that temperature is the most important variable for your hypothesis, but all of the literature suggests that it is oxygen, you can’t ignore oxygen and you should also frame your hypothesis using this variable (you can have more than one hypothesis after all!). In this case, you will also need to provide a sufficient introduction to temperature (using a logical argument and sufficient literature) as a variable to justify its inclusion in your hypothesis. Perversely, your aim is not to prove that your idea is right, but to show that the hypothesis can be refuted.

Progress is achieved through falsification of incorrect theories

We try to write a hypothesis that is falsifiable: i.e. you can prove (usually using statistical tests) that it is not correct (or at least show that the likelihood that it is correct is very low). That’s why it is conventional to provide the ‘null hypothesis’ that is the falsified version of the statement, suggesting that there is no relationship between the variables you have proposed to measure. The convention is to label this ‘null hypothesis’ H0, while the ‘alternative hypothesis’ (the one that says your variables are related as you suggested) is written as H1. When you formulate your hypothesis, it is traditional to write your alternative hypothesis to indicate the directionality of your tested variables. This way, the reader can simply imply that the null hypothesis is when there is no relationship, but this will need to be stated if the null hypothesis is more complex.

Karl Popper (2005) was the philosopher who proposed that without being able to refute or falsify a scientific problem, it ceases to be scientific. This is the reason for our null hypothesis. If the null is not available as a possible outcome, then logically, there is no science.

Karl Popper (2005):

“…it must be possible for an empirical scientific system to be refuted by experience”.

It is worth noting here that rejecting the alternative hypothesis, or accepting the null hypothesis, does not mean that you have proved your null hypothesis (Altman and Bland 1995). Using the same logic described above, testing your hypothesis has two potential outcomes: showing that the hypothesised relationship is likely to exist (accepting H1), or rejecting this relationship (rejecting H1). The other way of thinking of this is the widely used adage: Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

Most importantly, your hypothesis must come first, before you do the experiment or study. Hence the reason why this section comes at the start of part 2. Setting the hypothesis after the work is already done is fraudulent, and goes against the scientific method. Obviously, it isn’t fair to pose the hypothesis once you already know the answer (also known as HARKing). This is why there is so much emphasis put on formulating your hypothesis during your research proposal. Getting it right will determine what you do and how you test it. If you think of an extra hypothesis that would be really useful to test once you’ve already done your study, you can conduct a post hoc test, but this should have more stringent levels of statistical assessment.

4.1.2 How your hypothesis fits into the greater scientific community

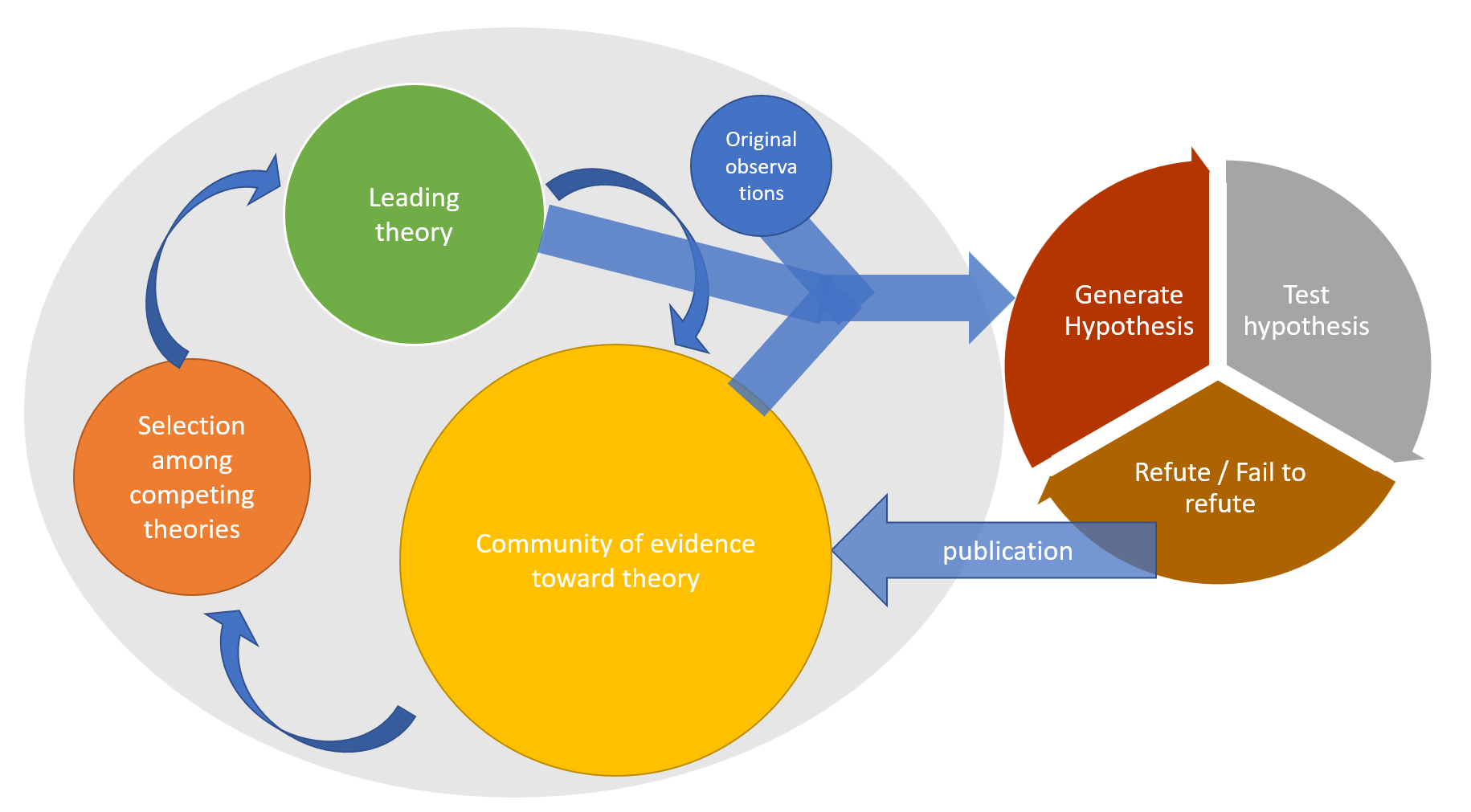

It is important to understand that hypotheses that you tests in your studies will ultimately become part of the wisdom of the greater scientific community, and ultimately the society at large (Figure 4.2). Of course, if you never publish your results, your work cannot be considered towards or against competing theories. Similarly, if you don’t read the recent literature, then you won’t be aware of what hypotheses have recently been tested and further how proposed theories are shaping up.

FIGURE 4.2: Hypotheses that you generate and test will join the community of evidence in the greater scientific community if published. When you publish chapters from your thesis, they enter into a community of knowledge (grey oval) held by the larger scientific community. This knowledge can be used to support or refute theories. The feedback from this larger body of evidence should come back into helping you generate more hypotheses for your own work.

Writing a hypothesis isn’t easy, but it is essential, and once you’ve understood what to do most of the rest of what you are writing for should make sense.

4.1.3 What a hypothesis isn’t

It is not a question and so should never have a question mark after it.

It isn’t a simple prediction: if this then that. You will see on the internet that hypotheses are explained in this simple predictive framework. I say that a hypothesis is not a simple prediction because it lacks the mechanistic and scholarly aspect of a good hypothesis, which is what we want to achieve.

4.2 Exercise 1: Spotting the hypothesis in a paper

Finding the hypothesis in a published paper should be an easy exercise. As we will see, there is a tradition that they hypothesis comes in the last paragraph of the introduction. However, there is no rule, so you might need to hunt around for it. I would hope that most authors actively advertise their hypotheses so that it is clearly indicated as such somewhere in the introduction.

In this exercise, you will take the five research papers that you selected for your keywords exercise and write down the hypothesis or hypotheses that are presented in each paper. Then, using what you have collected, answer the following questions:

- Are all of the statements hypotheses? (Are any of them questions or predictions?)

- Is it the null hypothesis (H0) or the alternative hypothesis (H1) that is given?

- How many hypotheses are presented in each paper?

- Does each hypothesis relate to a different experiment?

4.3 A formulaic way to start writing your hypothesis:

“If. then. because.”

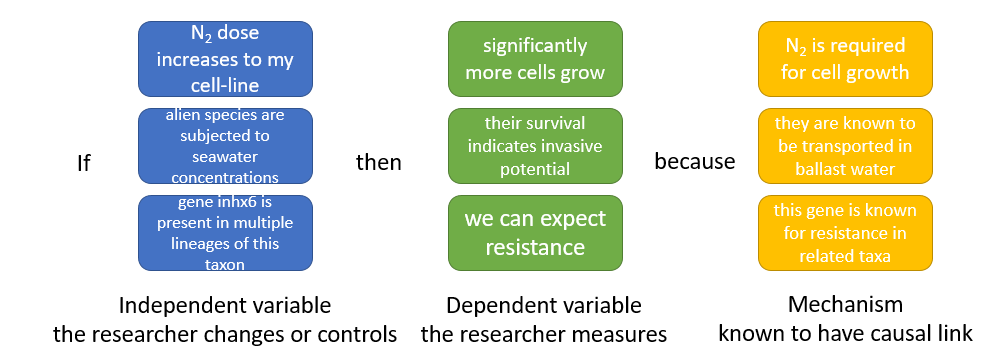

A simple way to consider making your hypothesis is to adopt an “If. then. because.” construction where you add in your problem statement using your independent variable after ‘if’, and your prediction using your dependent variable after ‘then’, and finally the expected mechanism after ‘because’. For example, using the “If. then. because.” construction, we might hypothesise: “If environmental temperatures in which tadpoles develop are increased then tadpole development rate is faster because they follow the classic metabolism of ectotherms”. Both independent variable (temperature) and dependent variable (tadpole development rate) are present in this hypothesis, and the predicted relationship between them is clear. In addition, the causal mechanism is stated. This is a formulaic way to start writing your hypothesis, because it usually ends up as an inelegant statement, which can be better refined for a reader. A citation for your stated mechanism might also help clarify exactly where the justification for this comes from. More examples of “If. then. because.” are shown in Figure (4.3).

FIGURE 4.3: If… then… because… is a formulaic way in which to start writing your hypothesis. The crucial parts that are required are all present including the variables that you control (independent variables), the measured variables (dependent variable), and the causal mechanism. The fabricated examples here are shown to help you get started. Remember that once you have your If. then. because. statement, you will need to refine it and add a citation for the known causal mechanism.

4.3.1 Dependent and independent variables

It is important to know what your variables are (Table 4.1). Choosing variables to manipulate and those to measure are going to depend on the literature; i.e., what other people have tried and found effective before.

| Variable name | aka | Variable description | Graphically |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent | Response, Outcome | The variable that you will measure to see how your treatments have changed it. | Shown on the y-axis |

| Independent | Determinate, Predictor, Explanatory | The variable that you will deliberately change and control in your experiment or sampling regime | Shown on the x-axis |

| Co-variate | Co-variable | An variable that is not of interest but that can influence the measurement of the dependent variable | - |

| Random variable | - | An variable whose value is unknown but can influence the measurement of the dependent variable | - |

4.3.2 What kind of mechanism are you using?

Mechanisms (or causal explanations) fall into three main areas: endogenous, exogenous and evolutionary (Allen and Baker 2017).

4.3.2.1 Endogenous causal explanations

Endogenous causal explanations focus on the mechanisms happening inside an organism, such as physiological processes, hormones, reproductive state, etc.

4.3.2.2 Exogenous causal explanations

Exogenous causal explanations concern mechanisms that are outside the body of individuals. Common exogenous mechanisms are climatic factors (temperature, humidity, precipitation, etc.) or may relate to the availability of food, predators or mates.

4.3.2.3 Evolutionary causal explanations

These mechanisms have evolved through time, and often relate to exogenous mechanisms triggering endogenous processes over multiple generations.

Note then that the above mechanisms are not mutually exclusive in their nature, and it may be useful to combine different approaches within biology to ask hypotheses across all of these levels. Mechanisms in biological sciences are rarely simple or act on multiple organismal levels, so designing a controlled experiment in order to test a specific mechanism thoroughly can be very demanding. In other words, can you be sure that the cause is really responsible for the effect that you are measuring?

A good hypothesis will often take an existing hypothesis further, to try to better refine the knowledge on a subject. Hence, it is perfectly acceptable to state that you are building on existing hypotheses (and giving the appropriate statement) when making your own.

4.3.3 Teleological versus causal hypotheses

A teleological argument refers to the reason or a purpose of a particular process. For example, you may measure vertical migration of water fleas and suggest that diurnal migrations are made because the water fleas want to avoid predation. This is a teleological hypothesis because you are suggesting that the reason behind a process is the desire by water fleas to avoid predators. Although a reduction of predation may be a consequence of vertical migration in water fleas, each water flea does not think about predation and then starts it’s upward movement as a result. A common mistake made in biology is to apply teleological arguments to processes that have no purpose or reason. Evolution is often mistakenly suggested to have a purpose (e.g. to evolve to a more advanced state), but in fact, evolution is not a goal-orientated process. There is no end-point to evolution, and evolution did not start in order to meet some predetermined form or function. On the other hand, a causal hypothesis focuses on the factors about A that cause B.

You should have realised that biologists are principally interested in causal hypotheses, because most mechanisms that are studied in biological sciences have no predetermined goal. If you are a behavioural ecologist, then you will need to be particularly aware of these two types of hypotheses, and when teleological explanations may be appropriate: many types of behaviour are goal orientated.

4.3.4 Tinbergen’s (1963) four questions

In his (1963) paper, Tinbergen posed four questions that he showed could be answered independently of each other, but that together could explain any observed biological trait. These questions are often laid out on a grid (Table 4.2) as this shows how they are pieced together to provide an explanation of the trait.

| - | Contemporary | Chronicle |

|---|---|---|

| Proximate | Mechanism: What is the anatomical or physiological structure of the trait? | Ontogeny: How does the trait develop in individuals? |

| Ultimate | Adaptive value: Why has the function of the trait influenced fitness? | Phylogeny: What is the phylogenetic history that led to the trait? |

Note that the first two questions are both proximate in that they explain the structure of the trait and its developed. The last two questions are evolutionary (or ultimate), to determine how the trait is influenced by selection.

Although Tinbergen (1963) originally conceived these questions to explore behavioural traits, these four questions are used more widely as big ideas that enable biologists to determine proximate and ultimate causes of any trait that they wish to study, either independently of each other, or in synthesis to provide an overall picture. If you haven’t done so already, it would be worth spending time to determine how many of Tinbergen’s four questions have been answered for your own study system.

4.4 Exercise 2: Breaking down a hypothesis

In this exercise, I want you to take the hypotheses that you recorded in Exercise 1 and work through the following set of objectives:

- Re-write each hypothesis into the form: “If… then… because…”

- Which is the dependent variable and which is independent? (Hint: If you have difficulty knowing this from the introduction, you can easily determine this from the Materials and Methods section)

- Once you have identified the components in each hypothesis, go back to the introduction and highlight where these three components (Dependent variable, Independent variable and mechanism) were introduced.

- Write out the missing (H0 or H1) hypothesis.

- Classify each hypothesis as endogenous, exogenous or evolutionary.

- Can you fit any of the hypotheses into one of Tinbergen’s four questions?

- What are the big ideas that these studies add evidence towards? (Hint: We will use this answer again in week 4)

You should be able to determine

4.4.1 The problem of independence

Probably one of the hardest issues that you will face in biological sciences is to determine whether your dependent variable is reliant only on the independent variable of choice. For example, a lot of variance in biological sciences will relate to the climate (especially with global change studies), but if the independent variable is temperature, this means that all other climatic variables must be kept the same. That is, if temperature is your independent variable, it is the only variable that can change in your experiment. This type of experiment is challenging as temperature often affects other variables (especially that they may vary in an unpredictable way). As soon as you have more than one independent variable, you can no longer test your dependent variable because you don’t know which independent variable it is reacting to. Isolating variables is notoriously difficult, especially when we move from the laboratory to the field. A classic approach to this is to consider additional variables as co-variates. A co-variate is not the variable of interest, but may change the dependent variable in your experimental design (Table 4.1). There are statistical ways to account for co-variates.

You will need to think very carefully about what variables other than those of interest are potentially impacted by your experimental design. If you cannot control for them, this will likely mean that you may need to change your hypothesis, or change your experimental design to take account of these co-variates. If you are unsure, then I would encourage you to look carefully at the experiments that others have conducted in the literature. You always need to know how you are going to analyse your results when you plan your experiment. Hence, ensuring that the analysis is accounting for all variables and co-variables and that these are all controlled for your chosen mechanism is a difficult but essential component of your hypothesis building exercise.

4.5 Exercise 3: evaluating a hypothesis

How do you decide whether or not a hypothesis is good? To do this, you might think that you need plenty of experience (and yes, that does help). But really, you just need to look for the elements that are discussed above. So once you’ve written your hypothesis, try to objectively answer the questions below:

- Is there a clear prediction with a mechanism (if. then. because)?

- Is the mechanism supported by the literature?

- Is the hypothesis testable/falsifiable?

- Does the hypothesis use concise wording and precise terminology?

- Does the prediction use independent and dependent variables correctly?

Consider each of the hypotheses from your example papers, and ask each of the questions above.

Question Were all of the parts of a hypothesis present? If not, then can you identify the missing parts of re-write an improved hypothesis for this paper?

Question How similar are the hypotheses presented to any of the hypotheses that you plan to test? Will you be using any of the same variables or mechanisms?

4.6 Summing up this hypothesis workshop

In this workshop, we have concentrated on the hypothesis as the central part of any research project. Of course, it is possible to conduct a scientific project without a hypothesis (see here), but you should now appreciate why your research will be stronger if it is falsifiable. You will have learned how to:

- find the hypothesis being tested in a research paper

- determine the components that make up the hypothesis and see how they are introduced

- evaluate the hypothesis and determine whether or not it meets the criteria of having independent variables, a mechanism supported by the literature, and if it is falsifiable

To take this forwards, you should now be thinking about how to formulate the hypotheses that you want to use in your own studies, From what you already know, gather together the variables of interest (you should go back and look at the keywords that you previously generated). Ask yourself:

- Has the hypothesis that interests you has been asked before?

- If so, how is yours different?

- If not, what are examples of similar hypotheses that have been asked?

- Does your hypothesis meet the criteria we have set out?

- If not, what can you change?

This is the end of this workshop on hypothesis building. If you find any problems with this workshop, please be sure to let me know. Email: jmeasey@ynu.edu.cn