Chapter 10 A formula for your discussion

Earlier in this course, we had a workshop on the formula of writing a chapter which concentrated on writing the introduction (see here). The discussion of a chapter differs from the introduction in many ways, but there is still a formula that you can use to get you started in writing your discussion. Here we concentrate on the discussion formula, and take the same approach that we did for the introduction with different exercises that you can use to help improve your understanding of the discussion.

10.1 Introduction vs Discussion

As the names suggest, the introduction and discussion have different purposes. While the purpose of the introduction was to introduce the aspects and components of the hypothesis to the reader, the discussion focuses on the interpretation of the results in light of existing literature. The introduction connected your hypothesis with the theme and topic of your subject area. Similarly, the discussion connecting your key findings into the perspective of the topic and theme. As you will see, there is still a heavy emphasis placed on the same aspects that we identified in the introduction. But in the discussion, we will attempt to place the outcome of testing the hypothesis into the context of our topic and theme. Simply, you state what you did and why it’s important.

From the outset, we need to acknowledge that the discussion is usually far less formulaic than the introduction. This is because when we come to discuss the outcome of our investigation, we may have varying amounts to say depending on how much literature already exists to compare our results to. Additionally, we may have important results or findings that are set apart from the original hypothesis, or even completely unrelated, that we feel deserve some discussion. Occasionally, these can even be more important than the hypothesis itself.

We set out to build a hypothesis that would provide input toward a community of evidence that would help our colleagues build a better theory (see Figure 4.2). Having explained to the reader why we wanted to test that particular hypothesis (in the introduction), we now want to tell the community how our results aid the community toward the most likely theory. We also want to suggest how future studies might be more likely to quickly generate support for the same theory. As Popper and Tarski found, once we have more evidence toward a particular theory, we can make more direct progress toward the truth by highlighting ‘correspondence to the facts’ and thereby directing studies that will more directly look for falsification (Veronesi 2014).

10.2 Your discussion formula

A lot of students, and even some academics will launch into the discussion with a jumbled set of ideas, and finish off on a point of irrelevance. Here I want to set out why having a discussion formula makes sense in relation to the rest of your chapter. To see the suggested formula, refer to Table 10.1.

| Discussion Paragraph | Description of contents |

|---|---|

| Paragraph 1 | Respond to your hypothesis |

| - | Provide a highlight of other important results |

| - | Mention supporting or conflicting literature |

| Paragraph 2 | Discuss the way in which your results impact the theme / topic |

| - | Use logical argument with existing results from literature |

| - | New insights given your findings |

| Paragraph 3 | The context of your results in the existing literature |

| - | Support and conflicting evidence |

| - | Use logical argument to determine how to interpret your results in the context of previous evidence |

| Paragraph 4 | Major caveats that impact on your methods, results and how this impacts your conclusions |

| - | Ways in which caveats might be overcome in future |

| - | Other important future studies arising |

| Paragraph 5 | Explain how your result adds to the evidence toward the theme (intro para 1) |

| - | Other important lessons learned |

| - | Take home message |

10.2.1 Responding to your hypothesis as the first paragraph

Your hypothesis is at the heart of your chapter (Figure 6.2), and as such it is something that you need to remind the reader of this primary importance right at the beginning of the discussion. This has been called creating a ‘memory-promoting structure’ to your discussion (Moore 2016). Since your first introduced your hypothesis, the reader has read all about how you went about testing it and the various results that your experiment has produced. Hence, at the start of the discussion you need to sum up your findings by accepting (or rejecting) your hypothesis.

Having this section at the start of your discussion allows impatient readers to skip from the introduction and immediately find the outcome. As a reader, there’s nothing more frustrating than an author who is withholding the outcome of their study, only prepared to give it right in the final sentence, or even worse to forget about it altogether. This is not a spoiler, it is really helpful to the reader. Indeed, many authors have taken to providing the outcome of their investigations at the end of the introduction so that the reader is fully aware of what the finding will be before they are reported.

If you don’t report the outcome of your hypothesis in the first paragraph of your discussion, then how will you discuss this finding? Just in the same way that providing a topic sentence at the beginning of a paragraph allows the reader to know what the paragraph is about, telling the reader the outcome of the hypothesis at the start of the discussion will provide them with context for the entire discussion, and remind them of the importance of what you were testing.

10.2.2 Evidence toward the best theory as the last paragraph

In your concluding paragraph, you should summarise the main findings of your study and link them to the objectives that you had in your introduction. We want to help our colleagues build the best possible theory and to work towards that in the shortest time (see Figure 4.2). Hence, the last paragraph of our discussion is going to set this out in a clear and concise way. If possible, we want to place our study in the context of the initial theme and topic that was set out in the initial paragraph of the introduction (see Table 6.2).

The concluding sentence of the last paragraph (and hence the last sentence of the discussion and of the chapter) needs special consideration. It should be concise and clear, carrying the most important information from the content. This will arm readers with the information that they need summing up the study with the ‘take home’ message that they can use in their own investigations.

10.2.3 The inbetween paragraphs

Although most commentators agree on the contents of the first and last paragraphs of the discussion, there are wide views about the order of what comes in between (e.g. Ghasemi et al. (2019)). This reflects the wide possibilities of points that could be discussed, and the preference of the authors for which they consider to be most important. Despite this, I am going to suggest that there is a logical formula as shown in Table 10.1. The reason for this is that by providing a pre-defined structure, it gives you a starting point for populating your discussion. It may be that later your advisor and co-authors have different ideas about which paragraphs will best follow the first.

Finding your story, also known as the metadiscourse, is often recommended as a way to organise the inbetween paragraphs (e.g. Ghasemi et al. 2019). When constructing the story of your study, you attempt to find logical connections between different parts of the text that you want to discuss. If you have already made an outline of your discussion, you should be able to read through this and find the best way in which paragraphs logically flow. Be aware that we are not talking about a literal story here, it is important in scientific writing that we avoid storytelling. Having said this, humans respond positively to stories over a set of statements, and it has been argued that introducing this kind of narrative element to scientific writing improves memory of the content (Angler 2020; Torres and Pruim 2019).

Biological Sciences often fall short in managing to specify the criteria of empirical support for a particular hypothesis or theory. In such cases, while explanations lack empirical support, we may be able to provide arguments about how they may possibly explain the observations that we have made. These “how-possibly explanations” are now recognised as important aspects in writing the discussion in biological sciences (Resnik 1991). “How-possibly explanations” satisfy the readers’ desire for knowledge on causation, even in the face of a lack of empirical evidence. Moreover, they allow the authors to build additional hypotheses that could be tested or refuted in additional studies, and in this way help the community move toward increasingly robust theories.

Once you have a plan for your inbetween paragraphs, and if you cannot find your story, try to sort the paragraphs in order of importance. I think that you are most likely to keep the attention of the reader in this way. Imagine, if your second paragraph consists of a bunch of uninteresting points, the reader may well stop reading thinking that there is nothing more interesting in the discussion. Once you’ve lost the attention of your reader, they are most likely to skip to the last paragraph to see if there is any interesting ‘take home’ message, or they might stop reading altogether. Hence, once you have completed the formula, you may want to sort the paragraphs logically and by perceived interest, according to your own study.

10.2.4 Ensuring that your discussion is balanced

The most consistent faults that I see in discussions submitted for peer review are that authors are loath to provide an honest and balanced discussion. Instead, it is most common to read an interpretation of the outcome of the study only in the way that the authors want it to be seen. As a scientific document, the discussion must provide a well thought-out, balanced argument that provides alternative ways of interpreting the results gained. Authors can provide a reasoned argument as to why their view is should be considered valid, but they must also provide the alternative interpretation. In some respects, not providing this balanced discussion insults the readers who may well aware of what the alternative position is. Moreover, it does a disservice to less experienced academics who are unaware of other potential interpretation. Having the maturity to be honest in the discussion section of your chapter is an important part of your own scientific development, signalling to others that you are aware of the strengths and shortcomings of your own study.

Michael Höfler and colleagues (2018) provide a nice overview of how to conclude findings based on substantive content with specified conditions. In doing so, they argue that this improves understanding of the causal mechanisms giving rise to the data, and the ability of researchers to address bias in future studies.

10.2.5 Inflating claims

Another common problem in discussion writing is making claims that are beyond the scope of your study. Usually, this is when the author claims to have provided all the evidence required to accept a hypothesis on the topic or even theme of their study, instead of simply providing evidence towards it. It is certain that some studies provide more evidence than others (e.g. larger effect sizes with greater sampling regimes). However, it is unlikely that any one study has the power to resolve a major theme, yet it is common to see such claims. Even published authors are quick to state the importance of their work (72%), over the limitations of their studies (24%) (Ioannidis 2007). Surprisingly, perhaps, this emphasis on importance is present in the instructions to authors for the publications reviewed, so that it’s hardly surprising that authors inflate importance in journals that have this as a criterion (Ioannidis 2007).

10.2.6 Acknowledging the limitations

Authors often avoid listing the limitations of their studies (Ioannidis 2007). The limitations are an important part of the discussion and aid the community of scientists to re-interpret the results (together with their limitations), and if possible seek new ways of designing studies without the same limitations in future. Note that limitations are not the same as errors, reproducability, biases, etc.

10.2.7 Avoid re-writing your results

In discussing our results, we often want to point at particular results in the discussion. However, many students fall into the trap of re-writing their results in the discussion. You need to be able to develop the skill of writing about your results, without writing out your results.

10.2.8 Other discussion issues

There are a lot more points to avoid and others to include in a discussion. You can find all of these in more detail here. Make sure that you read about the following:

10.3 Exercise 1: Spotting the formula in others’ discsussion writing

In this exercise we are going to take the 5 papers that were identified at the beginning of this course (see here). You can either print out these papers and work with coloured highlighter pens, or you can use the pdf versions in Acrobat Reader.

NB: If one or more of your papers are reviews, this exercise may not work for them. We will deal with literature reviews in another component of this course (here).

Unlike the previous exercise, this time we will Use the discussion and summarise each paragraph into the generalisations of Figure 10.1.

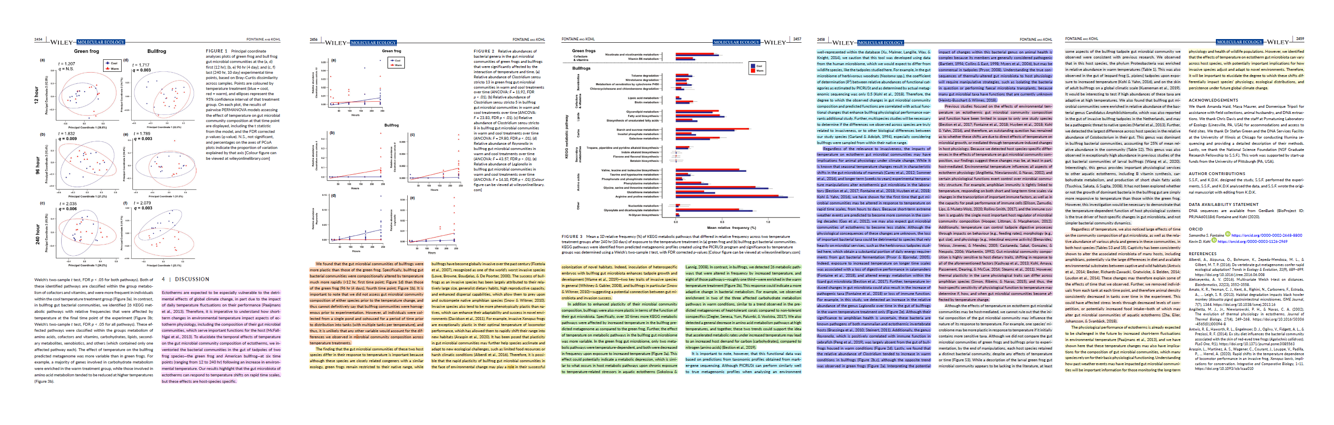

Here I have taken a paper from the Keyword Topics by Fontaine and Kohl (Fontaine and Kohl 2020).

FIGURE 10.1: De-constructing a published paper to spot the discussion formula. In this paper by Fontaine and Kohl (Fontaine and Kohl 2020) I have highlighted each paragraph in the introduction and broken it down into the formula given in Figure 6.1.

In this example, the theme is climate change, the topic is the microbiome, they key variable is temperature and the study system are two anuran species. But to keep it general I will use the words: theme, topic, variable, study system.

- Pink:

- Overview of importance of topic including key variables.

- Recap on what was done in the study

- Result highlight

- Orange:

- Respond to the hypothesis

- Specifics and major caveat

- Justifying argument

- Yellow:

- Importance of finding

- Relevance of finding in study system

- Relevance of finding and variable

- Green:

- Specifics around hypothesis result

- Specifics around hypothesis and key variable

- Blue

- Important caveat around limitations of method

- Future studies

- Purple

- Importance of result to theme

- Potential mechanisms that link result to theme

- Red

- Previous results in different study systems

- Grey

- Additional important caveat on findings and how they relate to the key variable

- Findings of interest outside the hypothesis

- Peach

- Additional results on the topic outside of the hypothesis

- Lemon

- Summing up the study

- Take home message and relationship with theme

Again, it was relatively straightforward to determine each of the components (above) from reading the text. This is a relatively long discussion, and yours maybe shorter. However, I would like you to conduct this breakdown of each discussion in each of your five papers.

Question How many caveats to the results can you find? (see Table 10.1)?

Question How many suggestions about future work or hypotheses to be tested can you find? (see Table 10.1)?

Question How much variation do you see of the typical discussion formula (see Table 10.1) within the five papers that you have chosen to look at?

Once you have answered these questions reflect on each of the discussions that you have read and ask yourself which was the best written discussion, and why? Are there particular parts of any of the discussions that you enjoyed. What were these? Similarly, did you feel that any part of the discussion was poorly written. Why? This is all part of critical reading - something that you should be doing for every paper that you read.

10.4 Exercise 2: Where are the different aspects discussed?

Almost every paper has different aspects, each of which requires discussion. These aspects are:

- theme This is the big idea that the study fits within. Most studies cannot directly study an entire theme, but only one topic within it. Examples of themes are: evolution, climate change, conservation, ecology

- topic This is a sub-discipline of the theme that usually determines that approach that you have taken to study the theme

- variable These are the units of measure and manipulation in the study

- study system This can be a cell, an organ, a species, a group of species, or an ecological system

- hypothesis The question that the study is designed to answer

For each of your five papers, I want you to name each of the aspects (use the same terms as used in the paper), and state which of the paragraphs in the discussion they first occur in. Record your results in a table like that given in Table 10.2 for the example from Exercise 1.

| Aspect | Name | Paragraph number | Frequency of mentions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | climate change | 6 | 2 |

| Topic | Microbiome | 1 | 56 |

| Variable | Temperature | 1 | 46 |

| Study system | Two anuran species | 1 | 30 |

| Hypothesis | “We found that the gut microbial communities of bullfrogs were more plastic than those of the green frog” | 2 | 3 |

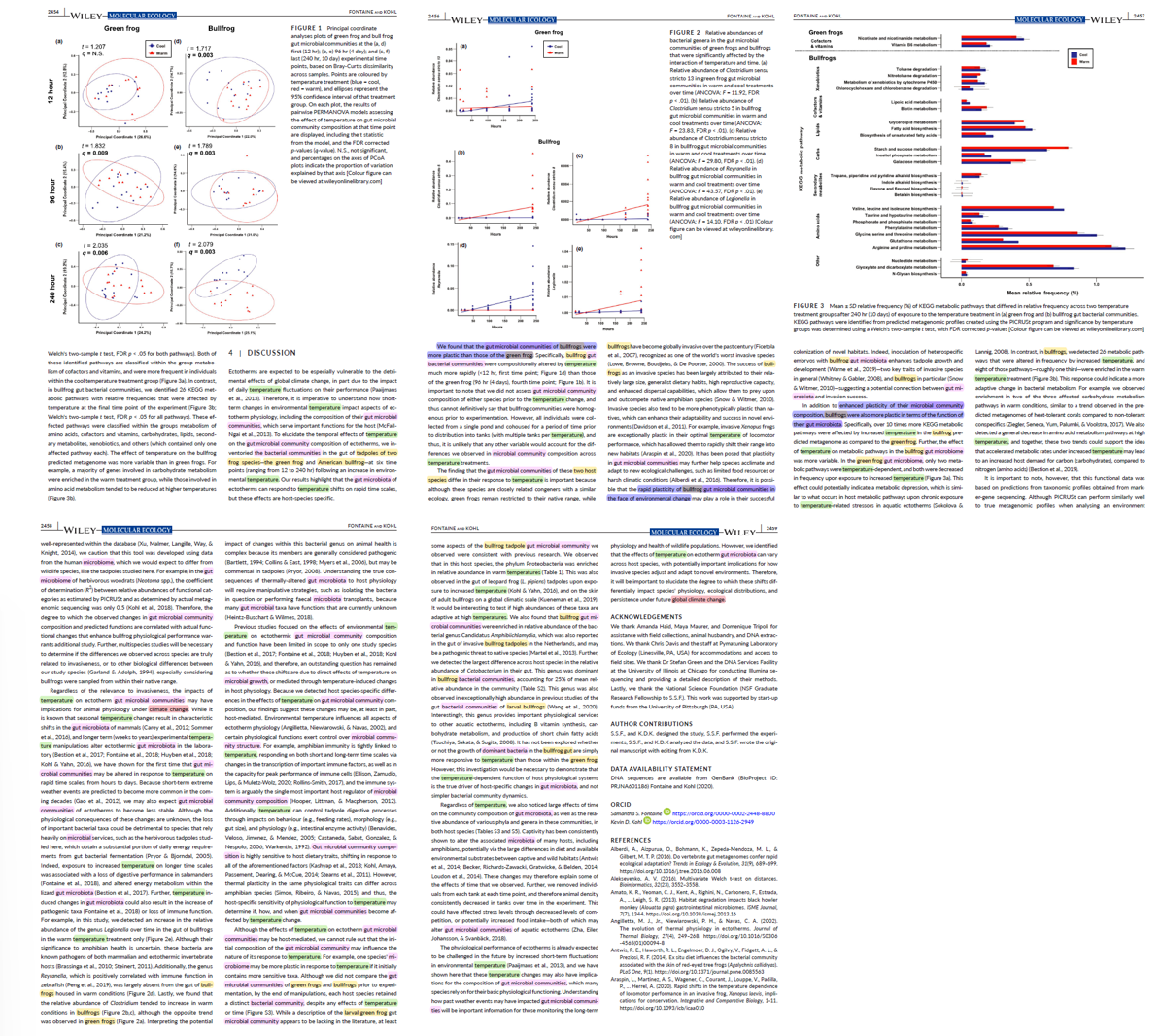

Once, again I have used Fontaine and Kohl (Fontaine and Kohl 2020) as the example and highlighted the theme, topic, variable, study system and hypothesis in Figure 10.2. Note how different the number of mentions of each aspect (Table 10.2) is vastly increased in the discussion compared to the introduction (Table 6.1), especially for the topic, variable and study system. Unusually, these authors respond to their hypothesis at the beginning of the second paragraph (Figure 10.2), after first restating the context for their study in the first paragraph. Climate change, as the theme, is now discussed several times, including the in final paragraph (Figure 10.2). The topic (microbiome) and key variable (temperature) are mentioned extensively in every paragraph of the discussion (Figure 10.2). Although the study system generally receives a lot more attention than in the introduction, there is an entire paragraph (#5) where the results are discussed with context from other study systems.

Note that it is important to retain the same words in the discussion that were defined in the introduction (and possibly also in the Methods), to remain consistent 1and facilitate the understanding of the reader. Constantly changing terms (like the names of the variables or mechanism) causes confusion for the reader. In this example, the authors are not shy of repeating the topic and variable names more than 100 times.

FIGURE 10.2: Distribution of the theme, topic, variable, study system and hypothesis in the introduction. In this paper by Fontaine and Kohl (Fontaine and Kohl 2020) I have highlighted the theme (climate change = red), topic (microbiome = pink), variable (temperature = green), study system (anurans = yellow) and hypothesis (blue). What is important here is not to see the individual words that have been highlighted, but the overall distribution of these different aspects within the discussion.

Question: Are the order of the paragraphs always increasing for each of your aspects in each of your five papers?

Question: What would be the result of changing this order, or inverting it?

Question: How much do your discussion results differ from those suggested in Table 6.2?

10.5 Starting to write with an outline

When you are ready to write your own chapter, or if you have already started, the way in which you go about this is to create the same sort of outline that we produced in Exercise 1.

Writing the discussion will come at the end of chapter writing. This will give you plenty of time to reflect while you are producing the introduction, methods and results. I like to have the discussion section present during all of this previous writing and dump ideas into it as I write. These generally include the importance of the findings, caveats and ideas for future studies, together with a bunch of literature that would make useful comparative citations.

Next, in the same way that you did for the introduction, order your existing thoughts into paragraphs (using Table 10.1 if possible), and give each sentence a bullet point. Add in pertinent literature. Keeping the first and last paragraphs static, ask yourself which of the intervening paragraphs are going to be most interesting for the reader. Then re-order the paragraphs as appropriate.

Have a discussion with your advisor about what you already plan to discuss and see if they have any more ideas. Once you’ve had their input, you can get writing and fill out your discussion with sentences. Don’t forget to plan each paragraph as we did in previous exercises.

10.5.1 Subheadings for important points

If your discussion falls into two or three subject areas, you may want to consider having subheadings for each section. When you are writting it definitely helps to use these. Once you have finished, you can make a judgement call about whether or not to keep them. When you submit your chapter for publication, the journal may allow subheadings in the discussion, or it may not.

10.6 Exercise 3: Where are the different aspects discussed?

The discussion funnels out from responding to the hypothesis to setting the results in the context of the theme. But unlike the hypothesis, there is room for more detailed discussion on the findings of your study that may not strictly resemble the funnel. In this exercise, we are going to do the same again, but to focus this time on the Discussion. The discussion should contain the same major aspects, but the emphasis this time is trying to reinterpret them in the light of the testing of your hypothesis.

Very simply speaking, the funnel of the introduction is now inverted within the discussion (Figure 6.1).

For each of your five papers, I want you to name each of the aspects (use the same terms as used in the paper), and state which of the paragraphs in the discussion they first occur in. Record your results in a table like that given in Table 10.2 for the example from Exercise 1.

Question: Are the order of the paragraphs consistent in each of your five papers?

Question: How much do your discussion results differ from those suggested in Table 10.1?

10.7 Writing the text

And once you have the fleshed out outline, it’s time to start writing your first draft. Remember that the best way to start writing is to do just that. It’s unlikely that your first effort will be the one that you will finally submit. But start writing. Then read, go back and polish. And keep polishing until you achieve your goal.

Although we have concentrated on the discussion in this workshop, the same basic approach to filling out the formula can be taken with the rest of the chapter. We will go through this later in the course, but if you want to read further now you can find this covered in How to write a PhD in Biological Sciences.

This is the end of this workshop on how to write your discussion. If you find any problems with this workshop, please be sure to let me know. Email: jmeasey@ynu.edu.cn